A well-crafted index is an easy-to-navigate, helpful tool for readers, leading them to the information they need to retrieve from a book in the shortest, quickest route. Not every book needs an index, but those with a user-friendly index allow the reader to find references to major and minor topics within the book and bring together scattered references to different aspects of the same subject and link related terms and synonyms. Without an index, the reader would have to sieve throughout the entire book in search of the needed information or guess where it might be located.

Why books need indexes? | Human indexers vs. software | Components | Pricing | When to hire an indexer? | Table of context vs. index | Before hiring an indexer

Provide the reader with effective access to information

Create a search tool superior to computer-generated indexes

Arrange the information into an easy-to-navigate sequence

Enhance the value of your book

Why does a book need an index?

Indexes to non-fiction books are like roadmaps that provide straightforward access to the information the reader seeks and to its related terms. Without an index, the knowledge enclosed on the pages of a book may become overlooked. A good index may enhance the book’s value, offering access to the information (minor and major in relevance to the book’s topic) contained in the book to the readers and users who are not familiar with the book.

Why do we still need human indexers if we can use indexing software?

Despite the advances in artificial intelligence, no automatic system can replace a human indexer’s intelligent analysis, subject-matter knowledge and empathy. Creating an index can be sped up using automated indexing tools, which help with alphabetisation, format and page-range elision style. But software cannot discern a passing mention from a critical term, and it will neither add synonyms to the index to create various search pathways. There are many other operations which, in contrast to software, a human indexer will carry out to create an effective and user-friendly index, such as:

- identifying implied concepts that are referred to in the text but not named directly,

- acknowledging references to variant word forms such as plural forms or alternative spellings,

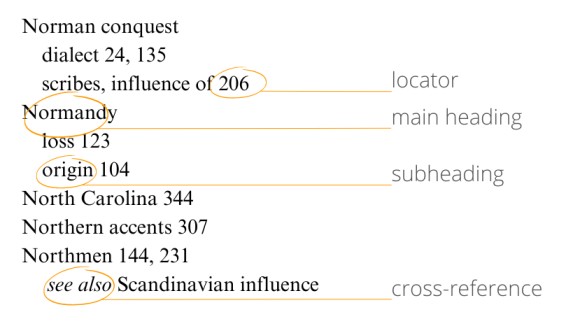

- creating context and recognise relationships between topics by providing see also cross-references,

- providing alternative access to terms using see cross-references or creating a double entry to synonymous terms,

- distinguishing between homographs (words that look the same but have different meanings), for example, bass (fish)/bass (musical instrument),

- distinguishing between important information and irrelevant references (passing references),

- pointing the reader to the information contained in images, figures or tables,

- taking into account the readers’ needs (to find information) and their levels of knowledge and other characteristics, such as education, age, language competence or literacy and digital literacy level.

The fifth edition of the Society of Indexers’ training course summarises the superiority of human indexing over automation:

There is no substitute for intelligent analytical indexing by a human indexer who has analysed the text in detail, identified the concepts discussed, recognized the inherent relationships between topics, anticipated the alternative approaches that might be made by users, provided pertinent entries with helpful modifiers and subheadings, and organized the whole into an efficacious arrangement so that the user can easily scan entries to find what they need.

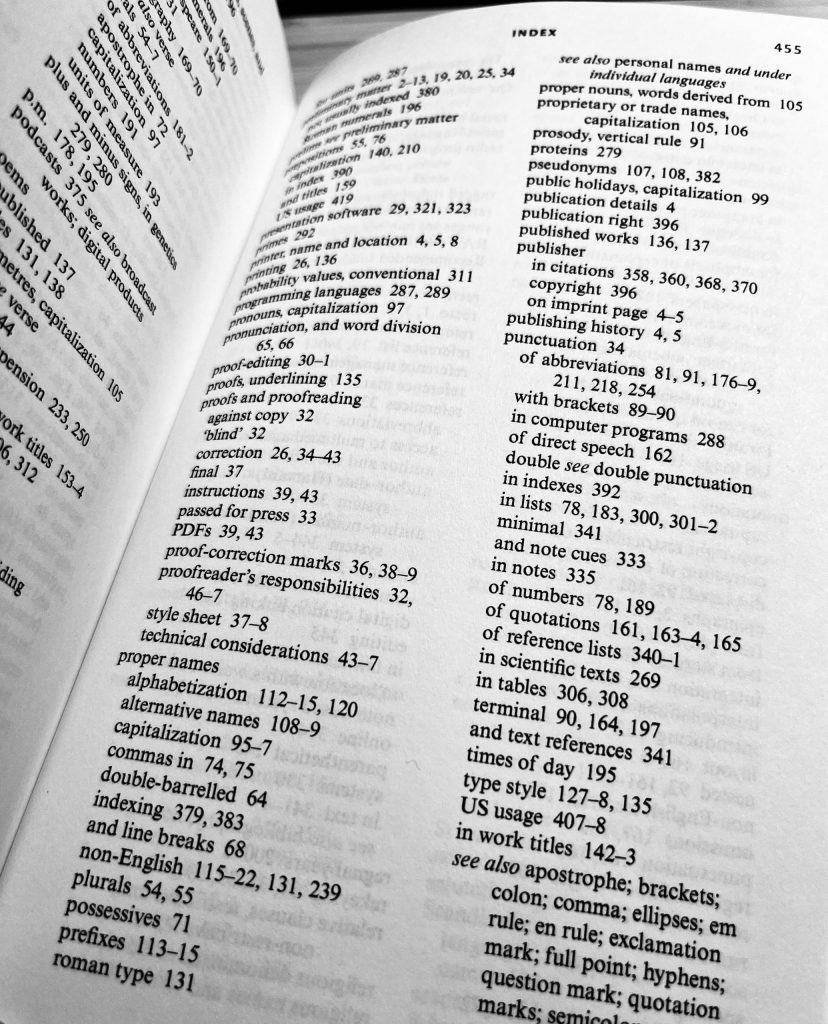

What does an index consist of?

An index contains terms arranged in an alphabetical sequence of entries. An entry usually consists of a heading with at least one locator and sometimes see and see also cross-references to one or more related terms. An entry may also contain a man heading followed by subheadings with locators and cross-references.

How long does it take to create an index?

Adequate index preparation requires ten–fifteen hours per 100 typeset pages or ten pages per hour. So, for example, a 300-page book will require around thirty–forty hours of preparation, depending on the text and the indexer’s experience and expertise.

How much does book indexing cost?

The Society of Indexers recommends indexing rates of £32.70 per hour, £3.65 per page or £9.90 per 1,000 words for an index to a straightforward, non-academic text. For instance, an index to such a book of 50,000 words would cost £495. This is only a rough estimation because several factors may affect an index’s time to completion and price. The complexity of the text, requiring the indexer to have an in-depth understanding of the subject matter, and a short deadline may increase the index’s price. Likewise, detailed indexing of figures and tables, content in a foreign language, a need to consult the author or late amendments to the text may increase the time needed to create an index.

Furthermore, indexing justifies these rates by demanding training and high-level of competency required. For instance, the Society of Indexers requires ten years of commercial experience as a criterion to receive the accreditation without enrolling on their training course. The course, on the other hand, takes, on average, two–four years to complete. The skills needed to become a good indexer are also numerous; they include the following:

- specialist knowledge,

- analytical reading,

- the ability to identify implicit concepts (not directly stated in the text) and relationships between topics,

- empathy to accommodate readers’ different search approaches,

- digital literacy skills,

- attention to detail,

- high-level literacy and language competency.

Experienced indexers will work faster and may quote higher rates if they have specialist knowledge (necessary when indexing academic books). Novice indexers (called student-indexers by the Society of Indexers) may take longer; however, their quotes will more likely adhere to the minimum rates suggested by the Society.

When should you hire an indexer?

Indexing takes place after the text is finalised and typeset when the author and editors have no more edits to make and the layout editor has typeset the manuscript. (A typeset manuscript version of the book is called a proof.) Thus, an indexer will work on the books’ proofs. Indexing often occurs simultaneously with proofreading, which also works with the proofs.

If you are, for instance, a self-publishing author engaging an indexer directly (rather than having the publisher sort out the index), remember to do it in advance. Finding a good indexer available to take on a new project might be difficult if you do not give them plenty of notice.

What is the difference between an index and a table of contents?

A table (list) of contents appears at the beginning of a book and arranges information contained in the book in the order in which they appear in the book. It is a useful, quick guide; however, it only lists the major divisions of the text (such as chapters and headings). On the other hand, an index appears at the end of a book, rearranges the information contained in a book, and gives the reader access to all of it, whether the piece of information is minor or major in relevance to the topic of the book.

What should you consider when hiring an indexer?

Effective indexing requires several skills:

- analytical reading skills,

- the ability to identify concepts not always directly stated in the text,

- ability to identify relationships between topics,

- empathy to accommodate readers’ different search approaches,

- digital literacy skills,

- attention to detail,

- high-level literacy and language competency,

- specialist knowledge.

To ensure the indexer possesses these competencies, it is worth checking their portfolio and client testimonials. Also, if they are a member of a professional editorial body, they are likely to have received formal training and follow a code of practice.

Find out about the indexer’s areas of expertise.

Indexers usually have in-depth knowledge of specific subject matters (these are their subject specialisms). This is because to create a good index, they must understand the text to be indexed and be familiar with its context. For instance, an indexer with a background in natural sciences may not be the best fit for indexing a manuscript about European history.

Learn about the indexer’s qualifications.

Joining a professional organisation that offers a peer network and training is one of the ways that indexers may gain qualifications and continue their professional development. Such organisations for indexers include the American Society of Indexers, the UK’s Society of Indexers, the Association of Freelance Editors, Proofreaders and Indexers of Ireland or the Australian and New Zealand Society of Indexers. So, when hiring an indexer, check if they are a member of any accredited organisation. In the Society of Indexers, Professional Members are indexers who have passed the Society’s training course or obtained suitable experience elsewhere.

Need a professional indexing service at affordable pricing?

Hire me