In academic writing, a research aim defines the central purpose of a study. It sets the direction for the entire project by stating what the researcher intends to achieve. A well-formulated research aim brings clarity, focus and coherence to all stages of the research process.

This blog post explains what a research aim is, how it differs from related elements such as objectives, questions and hypotheses and where it typically appears in academic texts. It outlines best practices for formulating a research aim, highlights common pitfalls and provides a step-by-step guide with examples. The post also covers how professional editing services can strengthen the presentation of a research aim for publication and recommends resources for further support.

Table of contents

- What is the research aim?

- Comparison with research objectives, questions and hypotheses

- What is the golden thread?

- Dos and don’ts of formulating research aims

- Formulate a research aim in 4 steps

- Editing services

- Resources

Key takeaways

- A research aim defines the main purpose of a study in one clear, declarative sentence.

- It differs from objectives, questions and hypotheses, each of which plays a distinct role.

- A strong aim uses precise language, aligns with the research problem and fits within the study’s scope.

- Common placements include the introduction of journal articles, theses, proposals and conference papers.

- The golden thread ensures alignment between the aim, methodology, findings and conclusion.

- Formulation should involve four steps: use an action verb, define the focus, add context and state the intended contribution.

- Copyediting improves clarity, tone and consistency; proofreading corrects errors and ensures the text is polished.

What is the research aim?

In academic writing, a research aim defines the primary purpose of a study. It clearly states what the researcher intends to achieve. Unlike research questions or objectives, which often break down the topic into smaller parts, it presents the overarching goal.

A strong research aim:

- focuses the scope of the study

- aligns with the central research problem

- guides the choice of methodology

- helps readers understand the study’s significance

Examples

- Literature: This research seeks to examine how modernist narrative techniques shaped representations of subjectivity in early 20th-century British fiction.

- History: The research aim is to investigate the social and economic impacts of land reform policies during the Meiji Restoration in Japan.

- Sociology: This study sets out to explore how social media use affects the formation of political identity among young adults.

- Education: The research aim is to evaluate the effectiveness of project-based learning in improving critical thinking skills in secondary school students.

- Environmental science: This study aims to assess the long-term effects of reforestation projects on local biodiversity in Southeast Asia.

- Public health: The research goals is to analyse the relationship between housing insecurity and mental health outcomes in urban populations.

- Computer science: This study sets out to develop a machine learning model for detecting online misinformation in real time.

Academic texts

Academic texts that typically include a research aim are journal articles, theses, dissertations, research proposals and conference papers.

- Journal articles: The research aim appears in the introduction, usually near the end, and sometimes in the abstract to summarise the study’s purpose.

- Theses and dissertations: It is stated in the introduction chapter, often in a dedicated subsection or just before the research questions.

- Research proposals: The aim is presented early in the proposal.

- Conference papers: It is included in the introduction, often in the opening or closing paragraph of that section.

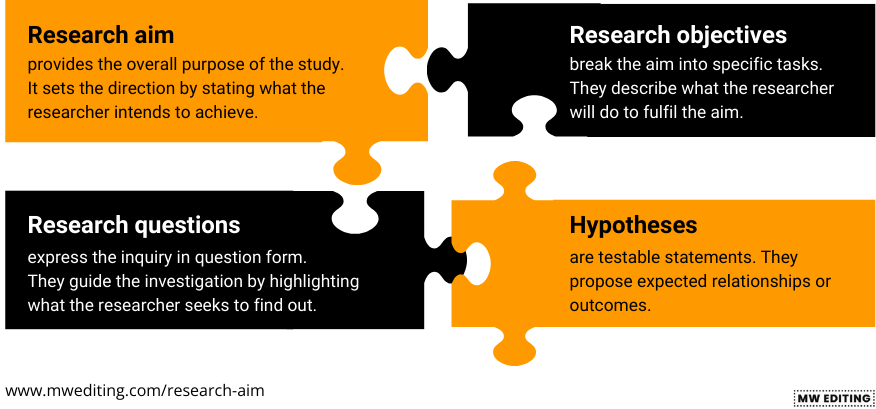

Comparison with research objectives, questions and hypotheses

In short, the research aim defines the goal, objectives outline the steps, questions focus the inquiry and hypotheses predict the results.

The research aim provides the overall purpose of the study. It sets the direction by stating what the researcher intends to achieve. For example, ‘This study aims to examine how climate policy influences public attitudes in urban areas.’

Research objectives break the aim into specific tasks. They describe what the researcher will do to fulfil the aim. For example, ‘To analyse media coverage of climate policy’ or ‘To survey urban residents on policy awareness.’

Research questions express the inquiry in question form. They guide the investigation by highlighting what the researcher seeks to find out. For example, ‘How does media framing of climate policy affect public opinion?’ or ‘What factors shape urban residents’ attitudes toward climate legislation?’

Hypotheses are testable statements, mostly used in quantitative research. They propose expected relationships or outcomes. For example, ‘Greater exposure to pro-environmental media coverage is associated with stronger support for climate policy.’

| Element | Purpose | Format | Scope | Placement in text |

| Research aim | States the overall goal of the study | Declarative sentence | Broad, overarching | Introduction (or abstract) |

| Research objectives | Break down the aim into specific, actionable steps | Short statements | Narrow, focused | After the aim, often as a list |

| Research questions | Identify what the study seeks to answer | Interrogative sentences | Thematic or analytical | In or after the introduction |

| Hypotheses | Make testable predictions about relationships or outcomes | If-then or declarative statements | Specific and measurable | In quantitative studies, often in methods or early results |

What is the golden thread?

In academic writing, the golden thread refers to the logical and consistent connection between the research aim, research questions, objectives, methodology, findings and conclusion. It ensures that every part of the study aligns with and supports the central purpose.

In the context of the research aim, the golden thread functions as follows:

- The research aim sets the direction.

- The objectives translate the aim into specific actions.

- The research questions clarify what the study will investigate.

- The methodology explains how the study will address the questions.

- The findings respond to the questions and reflect the aim.

- The conclusion ties the results back to the original aim.

Dos and don’ts of formulating research aims

In short, to write an effective research aim, use clear, focused and objective language that aligns with the research problem, avoids vagueness or multiple goals and distinguishes the aim from specific objectives.

When formulating a research aim, follow these key dos and don’ts to ensure clarity, focus and relevance:

Dos

- Do state a clear purpose: The research aim should describe what the study intends to achieve in one concise sentence.

- Do align it with your research problem: Ensure the aim directly addresses the core issue or question of the project.

- Do use precise and neutral language: Use terms that avoid ambiguity and reflect academic rigour.

- Do keep it focused and manageable: Avoid overly broad aims that lack specificity or cannot be addressed within the project scope.

- Do reflect the methodological approach: The research aim should suggest whether the study is explanatory, exploratory or analytical.

Don’ts

- Don’t list multiple aims in one sentence: A single research aim should express one central purpose, not several unrelated goals.

- Don’t use vague verbs: Avoid terms like ‘look at’ or ‘deal with’; instead, use actionable, clear verbs like ‘examine,’ ‘analyse’ or ‘investigate.’

- Don’t include value judgments: The research aim should not state what is good or bad but should remain descriptive and objective.

- Don’t confuse aims with objectives: The aim sets the overall direction; objectives break that aim into specific, actionable steps.

- Don’t phrase it as a question: Use a declarative sentence rather than a question format.

How to formulate a research aim in 4 steps

To formulate a clear and effective research aim, use a precise action verb, define the main focus, specify the context and state the intended contribution — all in one concise, declarative sentence.

- Start with a clear action verb: Choose precise verbs such as examine, analyse, investigate, assess, evaluate or explore. Avoid vague verbs like look at or deal with.

- Define the central focus: Identify the main issue, concept or phenomenon your study addresses. Keep it specific and relevant to your field.

- Add the context: Include the setting, population, period or geographical location if relevant. This helps narrow the scope.

- State the purpose or contribution: Explain briefly what the study hopes to reveal, improve, understand or contribute. This should reflect the significance of your research.

Research aim template

This study aims to [action verb] [main focus or phenomenon] in [context or setting] in order to [intended outcome or contribution].

Example using the template:

This study aims to investigate the impact of bilingual education policies on academic performance in secondary schools in Taiwan in order to inform future curriculum design.

Editing services

Professional editing services — copyediting and proofreading — offer distinct and complementary benefits when preparing academic texts for publication.

Copyediting

- Improves clarity and focus: Copyediting ensures the research aim is clearly stated, free from ambiguity and precisely worded, which helps readers understand the study’s purpose immediately.

- Refines academic tone and style: The copyeditor adjusts phrasing and structure to match the conventions of academic writing in the relevant discipline or target journal.

- Ensures correct terminology and consistency: Copyediting checks the use of terminology for consistency and clarity to avoid confusion or redundancy.

- Aligns with formatting and style guides: The research aim and surrounding text are edited to meet the requirements of style guides such as APA, Chicago or specific journal guidelines.

Proofreading

- Corrects grammar, spelling and punctuation: The proofreader identifies and fixes surface-level errors, ensuring that the researchaim and entire text are free from distracting mistakes.

- Checks formatting and layout: Proofreading confirms that elements such as headings, font use and referencing are consistent.

- Ensures final polish before submission: By reviewing the final version, the proofreader ensures the text is clean, professional and publication-ready, reducing the risk of rejection for preventable errors.

Resources

- How to Do Your Research Project by Gary Thomas, especially Chapter 5, focuses on shaping research questions and aims.

- How to Write a Lot by Paul J. Silvia includes practical strategies for writing and refining research aims and goals.

- PhD Life Raft podcast focuses on navigating the research process, including episodes on defining your research direction.

- Research in Action (Oregon State University) podcast discusses research design and communication, often addressing clarity and purpose.

- Rising Scholars provides free advice, courses and mentoring for researchers in the Global South, including support for framing research aims.

- The Craft of Research by Wayne C. Booth, Gregory G. Colomb and Joseph M. Williams offers detailed guidance on formulating research questions and aims within the broader research process.

- The Essential Guide to Doing Your Research Project by Zina O’Leary includes structured examples and common pitfalls in aim formulation.

- The Thesis Whisperer podcast covers writing strategies and common challenges in academic writing.

- They Say / I Say by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein is useful for understanding how to position your research aim within academic conversation.

- Vitae is a non-profit offering resources on research development, including guidance on writing research proposals and aims.

- Writing for Social Scientists by Howard S. Becker provides accessible advice on framing research and clarifying purpose.

Conclusion

Formulating a clear and focused research aim is essential for structuring a coherent and credible academic project. It defines the study’s purpose, guides its direction and connects all parts of the research through a logical thread. By applying the strategies and resources outlined here, researchers can improve the clarity, impact and publishability of their work.

Contact me if you are an academic author looking for editing or indexing services. I am an experienced editor offering a free sample edit and an early bird discount.