A research gap is an unexplored or insufficiently studied area within a particular field of knowledge. It represents unanswered questions, unaddressed problems or overlooked perspectives that existing research has not adequately covered. It is the first and crucial step in identifying a viable topic for a thesis, dissertation or research article, as it highlights where new research can contribute meaningfully to existing knowledge.

In academic research, identifying a research gap is the foundation for producing meaningful and impactful work. This blog post explores the concept of a research gap, its key characteristics and why recognising and addressing it is essential for academic writing. It provides insights into the different types of research gaps, from evidence and methodological gaps to contextual and application gaps, illustrating their significance in developing unique research contributions. Moreover, it outlines practical steps for identifying and evaluating research gaps and highlights how editing services, such as copyediting and proofreading, help refine research documents for publication.

- Research gap

- How to identify a research gap?

- How to evaluate the research gap?

- Next steps

- Research gap in academic texts

- Editing services

Research gap

A research gap is an unexplored or insufficiently addressed area in a particular field of study. It refers to unanswered questions, under-researched topics or overlooked aspects of a subject that existing studies have not fully covered. Identifying a research gap helps pinpoint opportunities for new research that can advance knowledge, solve problems or address inconsistencies in the current literature.

Key characteristics of a research gap

- Unanswered questions: Specific issues or questions that remain unresolved in the literature.

- Inadequate evidence: Areas where existing studies provide insufficient data or contradictory findings.

- Understudied populations or contexts: Research focusing on limited demographics, settings or variables.

- Emerging fields or topics: Subjects where little to no research has been conducted due to novelty or recent developments.

- Theoretical or methodological limitations: Gaps caused by reliance on outdated theories, frameworks or research methods.

Why identifying a research gap is important?

- It justifies the relevance of the study.

- It ensures originality by avoiding redundancy.

- It helps focus the research on areas that need further exploration.

- It contributes to the progression of knowledge in the field.

Types of research gaps

Research gaps can take various forms, depending on the type of limitations or gaps in existing knowledge. Understanding these types helps researchers identify the most relevant area for investigation when developing a topic for a thesis, dissertation or research article.

Evidence gap

- Occurs when there is a lack of sufficient data or studies on a particular topic

- Example: Limited studies on the impact of social media on rural populations compared to urban populations

Knowledge gap

- Exists when certain aspects of a topic are not well understood or explored

- Example: Limited understanding of the long-term effects of a specific treatment in healthcare

Theoretical gap

- Arises when existing theories fail to adequately explain a phenomenon or when there is no theoretical framework for a particular issue

- Example: A theory developed in one context (e.g. Western economies) that has not been tested in another (e.g. developing economies)

Methodological gap

- Involves limitations or inconsistencies in the methods used in previous studies, leading to unexplored areas that require a different approach

- Example: Over-reliance on quantitative methods without exploring qualitative perspectives in studying consumer behaviour

Contextual gap

- Appears when research focuses predominantly on certain populations, geographies or conditions, neglecting others

- Example: Studies on climate change effects primarily in developed nations while ignoring developing countries

Population gap

- Exists when certain groups or demographics are underrepresented in research

- Example: A lack of studies addressing the experiences of older adults in the gig economy

Application gap

- Occurs when research findings have not been applied or tested in practical or real-world scenarios

- Example: Theoretical models of renewable energy adoption that have not been implemented in real urban planning projects

Contradictory evidence

- Arises when existing research presents conflicting findings, indicating a need for further investigation to clarify the issue

- Example: Studies showing both positive and negative impacts of remote work on productivity

Technology gap

- Found when new technologies or advancements have not been studied in depth or applied to existing problems

- Example: Limited research on how artificial intelligence can improve traditional educational models

Policy or practice gap

- Exists when research does not address its implications for policy or practice or when there is a lack of studies linking research findings to real-world decision-making.

- Example: Studies on workplace diversity that do not explore how findings can influence organisational policies.

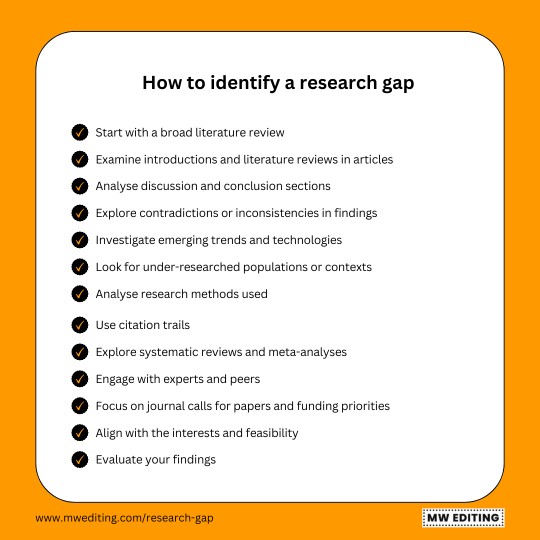

How to identify a research gap?

Identifying a research gap involves a systematic approach to reviewing existing literature, analysing its limitations and pinpointing areas where further research is needed. Below is a breakdown of specific, tangible steps to help identify a research gap:

1. Start with a broad literature review

- Explore recent and key studies: Begin by reviewing foundational and recent papers in the field to understand the state of research. Use academic databases such as Google Scholar, PubMed or Scopus to gather articles.

- Focus on review articles: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses summarise existing studies and often highlight gaps or unresolved questions.

2. Examine introductions and literature reviews in articles

- Identify what is already known: Read how authors summarise the current state of research in their introductions and literature reviews.

- Spot the ‘gap statements’: Look for phrases like ‘little is known about,’ ‘further research is needed’ or ‘this has not been studied in X context.’ These often point directly to research gaps.

3. Analyse discussion and conclusion sections

- Look for suggestions for future research: Authors frequently propose follow-up questions or areas for further investigation.

- Check for limitations: Study the limitations section to identify where current research is lacking, such as methodological weaknesses, small sample sizes or narrow contexts.

4. Explore contradictions or inconsistencies in findings

- Compare studies on the same topic to identify areas where results conflict.

- For example, if some studies suggest a positive relationship between variables and others find no correlation, this could indicate a gap worth exploring.

5. Investigate emerging trends and technologies

- Explore new developments in the field that have not yet been studied extensively. For example, recent advancements in AI or climate change policies might open new avenues for research.

6. Look for under-researched populations or contexts

- Identify groups, regions or conditions that are under-represented in existing research. For instance, research conducted in developed countries may not apply to developing regions.

7. Analyse research methods used

- Identify methodological gaps: If most studies in a field rely on quantitative methods, consider whether qualitative approaches could yield new insights.

- Examine data sources: Look for gaps where alternative or richer data could improve understanding.

8. Use citation trails

- Follow references in key papers: Check the studies cited by foundational papers to uncover related topics or less-explored areas.

- Check who cited the paper: Use tools like Google Scholar to find newer research that builds on a specific study and explore the gaps they identify.

9. Explore systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- These papers summarise multiple studies on a topic and often highlight areas where research is limited or contradictory.

10. Engage with experts and peers

- Discuss the area of interest with supervisors, colleagues or domain experts. They may suggest unexplored questions or directions.

- Attend academic conferences and webinars to learn about ongoing debates or under-researched areas.

11. Focus on journal calls for papers and funding priorities

- Check special issues: Academic journals often publish calls for papers on specific themes, which may point to emerging gaps in the field.

- Review funding opportunities: Research grant announcements often indicate areas that funders see as high-priority or under-researched.

12. Align with the interests and feasibility

- Ensure the gap you identify aligns with the interests, expertise and resources. A manageable and compelling gap is essential for producing high-quality research.

How to evaluate the research gap?

Evaluating a research gap is essential to ensure that pursuing it will result in a feasible, impactful and original study. The following criteria can help evaluate a research gap comprehensively:

Originality

- Question: Does addressing this gap lead to original contributions to the field?

- Evaluate whether the gap has already been extensively studied or if the approach adds something new (e.g. a novel methodology, context or perspective).

Value/Significance

- Question: How important is the gap to the academic field or society?

- Consider if filling this gap will provide valuable insights, advance theory or solve practical problems.

- Evaluate whether the research aligns with current trends or pressing issues, increasing its relevance.

Data access

- Question: Is the required data readily available or can it be realistically obtained?

- Assess whether you have access to reliable sources, participants or secondary datasets to conduct the research.

- Ensure ethical and legal approval for data access, especially for sensitive information.

Equipment

- Question: Do you have access to the tools, technology or facilities needed for the research?

- Confirm whether you can obtain necessary equipment within the budget and timeframe or consider alternatives if resources are limited.

Timeframe

- Question: Can the research be completed within the given deadline?

- Consider whether the scope of the gap is manageable within the programme’s time constraints (for instance, 6 months for a dissertation, 3–5 years for a thesis).

Literature

- Question: Is there enough existing literature to support the research?

- Ensure the gap is grounded in a robust body of work to provide context and justify the study.

- Conversely, avoid gaps that lack sufficient background literature, as this could indicate weak relevance.

Supervisor

- Question: Does the supervisor have expertise in this area and can they guide you effectively?

- Evaluate whether the chosen research gap aligns with the supervisor’s knowledge and research interests.

- Ensure their availability for regular feedback and support.

Ethics

- Question: Are there ethical considerations and can they be addressed?

- Evaluate whether the research involves sensitive topics, vulnerable populations or potentially controversial methods.

- Confirm whether the study complies with institutional and legal ethical standards.

Personal appeal

- Question: Are you genuinely interested in the topic?

- Assess whether the gap aligns with the academic goals, personal interests and career aspirations.

- Personal motivation is crucial for sustaining effort over the course of the project.

Risk

- Question: What are the potential risks and can they be mitigated?

- Consider potential challenges like low response rates, equipment failure or unexpected results.

- Evaluate contingency plans to address these risks.

Other practical considerations

- Funding: Determine if the research requires funding and whether sufficient support is available.

- Collaboration: Evaluate the potential for interdisciplinary or institutional collaborations to enhance the study.

- Scalability: Assess whether the research can be scaled up for future projects, such as a publication or follow-up studies.

Framework for evaluation

Use a simple scoring system (for instance, 1–5 or low/medium/high) to rank each factor based on feasibility and importance. Summarise the evaluation to identify whether the gap is viable.

Example evaluation table

| Criterion | Score (1–5) | Comments |

| Originality | 5 | Novel context not previously studied |

| Value/Significance | 4 | Relevant to current policy debates |

| Data access | 3 | Requires permission from institutions |

| Equipment | 4 | Tools available in the university lab |

| Timeframe | 5 | Can be completed in 1 year |

| Literature | 4 | Strong theoretical foundation |

| Supervisor | 5 | Experienced in the field |

| Ethics | 3 | Needs careful approval for sensitive data |

| Personal appeal | 5 | Aligned with career goals |

| Risk | 4 | Moderate but manageable risks |

Next steps

After identifying a research gap for the thesis or dissertation, the short-term next steps involve refining the gap into a researchable focus and setting up the foundation for the study.

1. Clarify the research question or problem statement

- Draft a clear, concise question that directly addresses the gap.

- Ensure it is specific, manageable and aligns with the study’s scope.

2. Refine the research objectives

- Break down the research question into concrete aims or objectives.

- Ensure they are actionable and measurable.

3. Review the literature again with focus

- Revisit the key studies related to the gap for deeper insights.

- Identify relevant theories, frameworks or methods that can inform the research design.

4. Draft a preliminary outline

- Create a working structure for the thesis or dissertation, including chapters like:

- Focus on these initial chapters for now.

5. Write a research proposal

- Summarise the research gap, the question, objectives and methodology in a concise proposal.

- Submit it for approval by the supervisor or academic committee if required.

6. Develop the methodology

- Decide on the research design (qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods).

- Plan the methods for data collection and analysis.

- Identify necessary tools, data sources or participants.

7. Plan a timeline

- Break the project into immediate tasks (e.g. completing the literature review, designing the methodology).

- Set deadlines for these tasks, focusing on the next 1–2 months.

8. Seek feedback

- Share the research question, objectives and preliminary ideas with the supervisor.

- Incorporate their feedback to refine the focus.

9. Address ethical considerations

- Begin drafting ethical approval documents if the study involves human participants, sensitive data or other ethical concerns.

10. Start writing the introduction and literature review

- Begin drafting the introduction to frame the research gap and objectives.

- Expand the literature review to provide context and justify the importance of the study.

Research gap in academic texts

Finding a research gap is essential for writing academic texts where originality and contribution to knowledge are crucial. Here are the primary academic texts where identifying a research gap is necessary:

- Thesis or dissertation requires a unique contribution to the field, whether at the undergraduate, master’s or doctoral level. Research gap justifies the research question and establishes the significance of the study.

- Research articles are peer-reviewed journal articles, which aim to contribute new findings, insights or methodologies. Research gap highlights the originality of the study and its relevance within the existing body of work.

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses synthesise existing research to identify patterns, gaps and areas requiring further exploration. Research gap drives the motivation for the review, outlining why synthesising the literature is necessary.

- Grant proposals for funding must justify why the research is needed. Research gap demonstrates the project’s significance and how it addresses a pressing issue.

- Conference papers often aim to present new ideas or preliminary findings. Research gap validates the importance of the study within ongoing academic discussions.

- Monographs explore a specific research area in depth. Research gap ensures the book provides fresh insights and fills a significant void in the literature.

- Policy papers and white papers propose solutions to practical issues based on research. Research gap identifies gaps in evidence or practice to justify the need for policy recommendations.

- Essays or research reports are common in undergraduate programmes; they analyse or summarise research findings. Research gap frames the essay or report around a meaningful focus rather than reiterating established knowledge.

Editing services

Professional copyediting and proofreading services focus on refining academic documents to ensure they are polished, professional and publication ready.

Copyediting involves improving the clarity, coherence, style, tone, grammar and sentence structure of a document. It focuses on refining the content at a deeper level, ensuring readability, consistency and alignment with academic or style guidelines.

Proofreading is the final review of a document to catch minor errors such as typos, grammar mistakes, punctuation issues and formatting inconsistencies. It ensures the text is polished, error-free and ready for submission or publication.

Clarity

Copyediting focuses on improving sentence and paragraph-level clarity. Editors rewrite or restructure sentences to eliminate ambiguity, awkward phrasing and overly complex language. This ensures that the document’s arguments and ideas are presented in a logical, straightforward and understandable manner.

Consistency

Proofreading ensures that terminology, abbreviations, formatting (e.g. headings, subheadings and citations) and style are applied consistently throughout the document. It addresses small but crucial details, such as ensuring consistent spelling (e.g. UK vs US English) or standardising reference formatting according to the required style guide.

Accuracy

Copyediting plays a crucial role in ensuring grammatical accuracy and proper sentence structure. Editors correct common grammatical issues such as subject-verb agreement, tense consistency and misplaced modifiers, ensuring the text adheres to academic writing norms. Additionally, they improve syntax by restructuring sentences for better flow and readability. For example, overly long or fragmented sentences are adjusted to maintain logical coherence. This attention to grammar and syntax helps present the arguments with precision and professionalism, avoiding miscommunication or ambiguity.

Typographical errors

Proofreading is the final safeguard against typographical errors that might detract from the document’s credibility. These errors can include misspellings, repeated words and misplaced letters or numbers in tables, figures or captions. Proofreaders check for these issues, which may have been overlooked in earlier drafts. For example, a misplaced decimal point in numerical data or a typo in a key term can undermine the accuracy of the work. By eliminating such errors, proofreading ensures the document maintains its professionalism and reliability.

Style and tone

Copyediting ensures that the style and tone of the writing align with the expectations of the academic discipline and target audience. Editors standardise the language to maintain an objective, formal and professional tone, removing casual expressions or overly complex jargon that might confuse readers. They refine the word choice, ensuring it is precise and appropriate for the subject matter. For instance, technical terms are preserved for accuracy, while redundant or verbose phrases are streamlined. This ensures the work meets the conventions of scholarly writing and appeals to academic reviewers or readers.

Punctuation

Proofreading addresses punctuation issues, such as misplaced commas, misused semicolons or incorrect quotation marks, which can alter the meaning or readability of sentences. For example, proofreaders ensure that colons and semicolons are used appropriately to separate clauses and quotation marks are formatted correctly for direct citations or quotes. Attention to punctuation also extends to references and citations, where proper placement of periods, commas or brackets is critical to comply with style guide requirements. This meticulous review enhances the document’s overall readability and adherence to formal academic standards.

Formatting compliance

Copyediting ensures that the document adheres to the formatting requirements of the target journal, institution or publisher. Editors review headings, subheadings, font sizes, line spacing, margins and citation styles to ensure consistency and alignment with specific guidelines (e.g. APA, MLA or Chicago). They also standardise the formatting of figures, tables and captions to create a professional appearance. For instance, inconsistencies in reference styles (e.g. italicising journal names in some cases but not others) are corrected to avoid confusion. This level of detail enhances the document’s credibility and ensures smooth submission.

Document readiness

Proofreading provides the final review to ensure the document is error-free, polished and ready for submission or publication. Proofreaders meticulously check the entire document, ensuring all previous corrections have been applied consistently and no new errors have been introduced. They confirm that all sections of the document are complete, formatted correctly and aligned with submission guidelines. For example, they ensure that page numbers match the table of contents, all references are included and appendices are formatted consistently. This final step guarantees that the document meets the highest standards of professionalism.

Key takeaways

Identifying a research gap is a vital step in academic writing, guiding researchers toward original and relevant contributions to their field. This guide has explored the nature of research gaps, their types and their importance in various academic texts such as theses, dissertations and journal articles. By following systematic methods for identifying and evaluating gaps, researchers can focus their efforts on addressing unexplored areas effectively. Additionally, employing professional editing services ensures that the final document meets the highest standards of clarity, consistency and professionalism.

Contact me if you are an academic author looking for editing or indexing services. I am an experienced editor offering a free sample edit and an early bird discount.